What is Leverage?

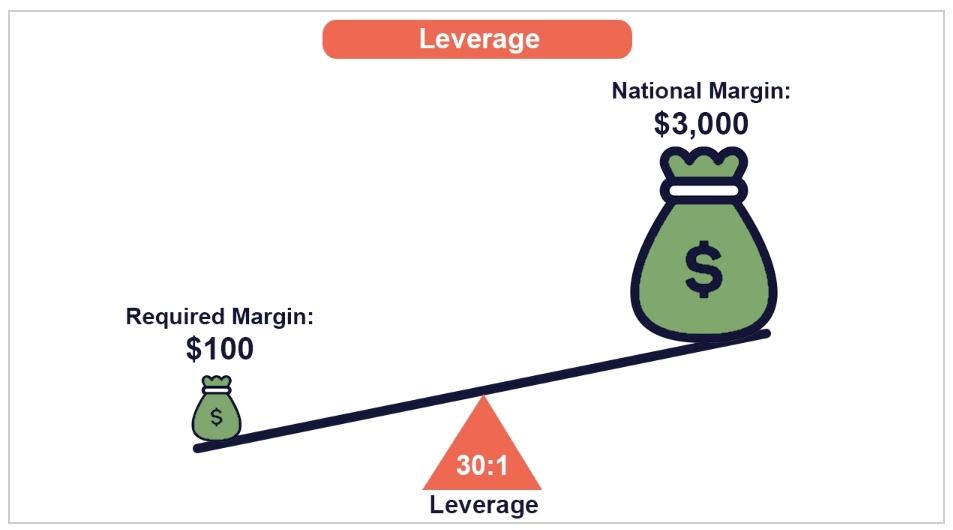

Leverage is the purchase or sale of an asset, with part of the price paid by the investor and the rest covered by the lender. In this case, the asset becomes collateral for the loan, and the lender receives interest on the advance amount for the term of the loan.

Under such an agreement, the investor is the only party that either makes a profit or suffers a loss from owning the asset.

How do these deals work?

Leverage allows an investor to buy more securities than when using cash alone, increasing the potential gain but also the loss.

In brokerage accounts, this is called buying or selling on margin. Stock brokers usually allow clients to use their accounts at a 2:1 ratio. In practice, this means that if an investor has $500 cash on margin, they can purchase $1,000 worth of securities.

If the value of the securities rises to $1,100, the investor can sell the securities for a profit of $100, resulting in an account balance of $600 less interest paid to the brokerage. If the value of the securities falls to $900 and the investor closes the position, he will incur a loss of $100 on a $400 account, minus the interest paid to the brokerage.

If the value of an asset falls and the investor retains ownership, he must ensure that there is enough capital in the account for the maintenance margin. In the case of a margin call, the investor will need to add capital to the account.

When is leverage used?

When buying real estate, leverage is used in most cases. Buyers are typically required to pay 20% to 30% of the property’s value, with the bank paying the remainder, a 20% down payment and an 80% loan with a leverage ratio of 5:1. In this case, homeowners are more exposed to the ups and downs in the real estate market, which often leads to an increase in percentage and capital losses for housing.

Companies also use leverage to acquire other companies. When a company uses a large amount of debt to buy another, it’s called a leveraged buyout. In this case, the buying company may be required to pay only 10% of the rate, with the remaining 90% from the lender and/or the bond sale.

In such transactions, bonds are often not classified as investment grade due to the degree of risk involved. The bonds’ higher default risk is reflected in the unusually high interest rates paid by the buying company, classifying them as junk bonds.